Vernon Street

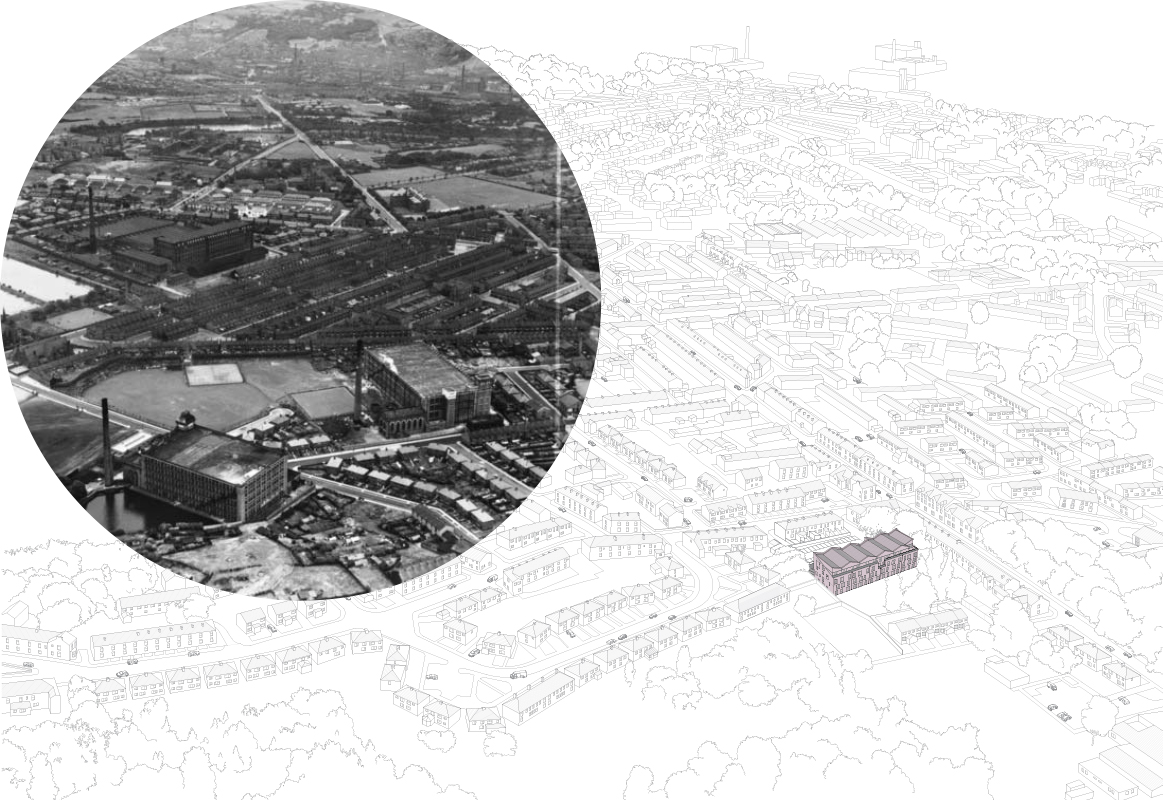

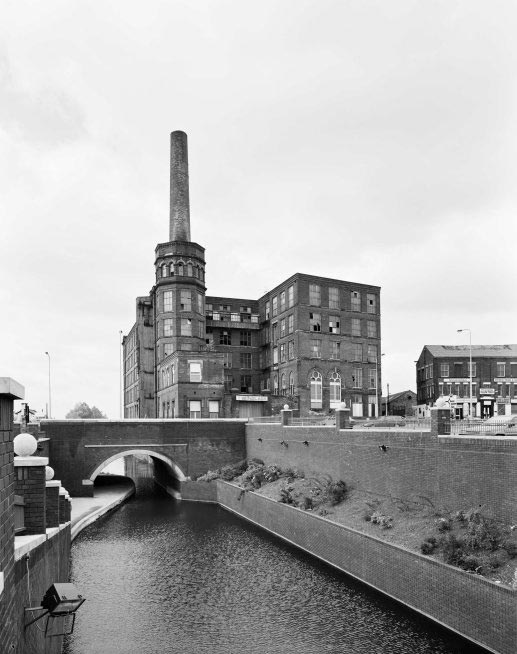

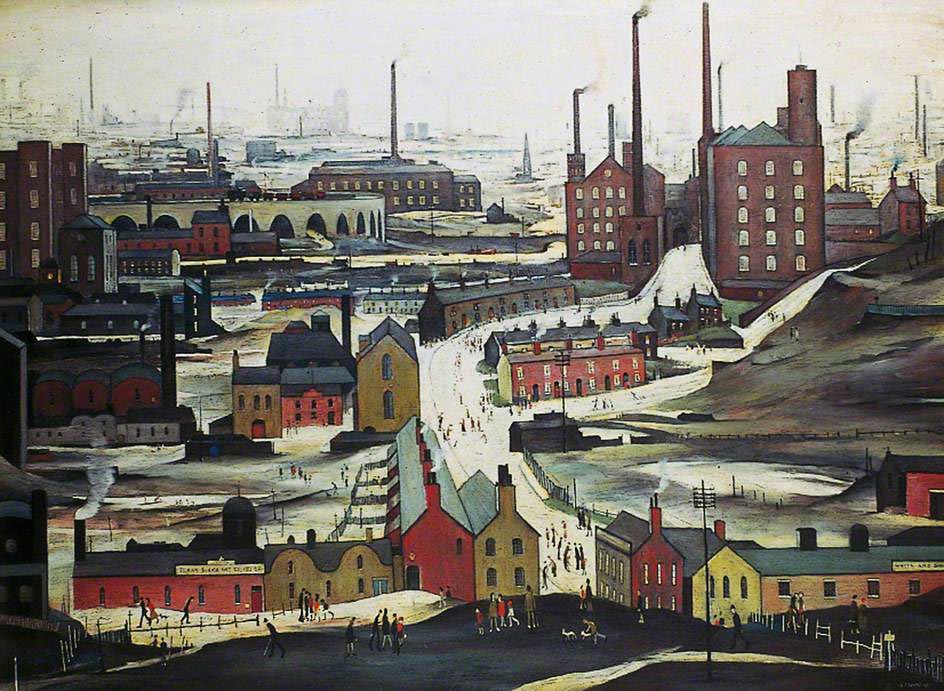

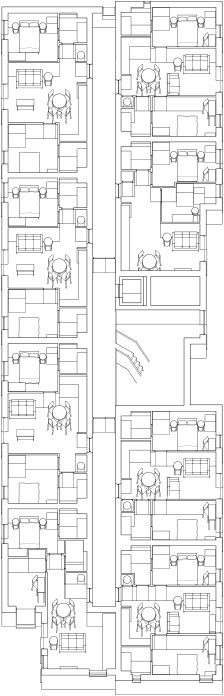

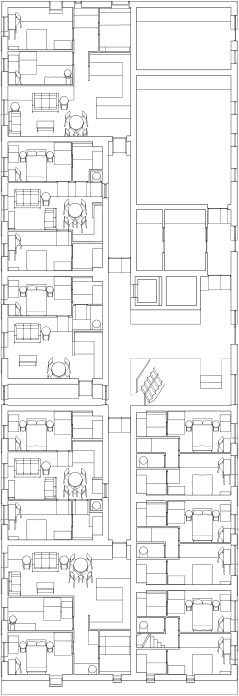

An examination of C19/ 20 Ashton-under-Lyne shows a landscape characterised by large-scale industrial buildings, great monolithic mills and factories with their smokestacks, surrounded by housing arranged in linear row forms; the ubiquitous terrace. There is a clear social relationship between the modest two-storey dwelling and the larger industrial building, mass employment underpinned the development of mass housing in dense settlement patterns. A formal relationship can thus be observed also between the monolithic block form of the mill or factory, against the surrounding two-storey terraced housing.

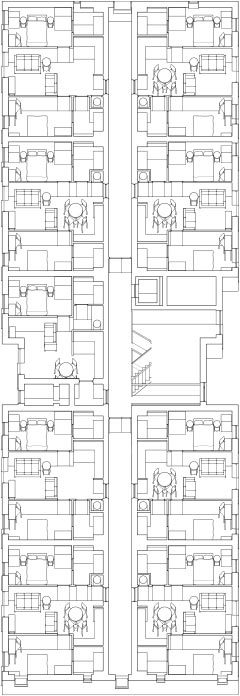

Writing in the Architectural Review in 1955, Ian Nairn famously complained that the specificity of places was being eroded such that “…the end of Southampton will look like the beginning of Carlisle.” More recently, critic Jack Self has observed that “form follows finance”. These statements evidence a call to action, to deliver housing of the quality and quantity required to meet local needs, in forms that embody specific narratives of place.

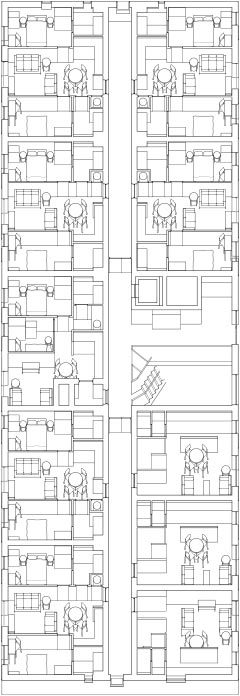

It does not follow that mere repetition of an immediately adjacent form, nor imposition of a universal model, in a polite and contextually complementary material, will deliver an appropriate response to the particularity of a setting; rather a project should seek to establish narrative connections to place though form and material, to seek to embody what often may no longer be seen.

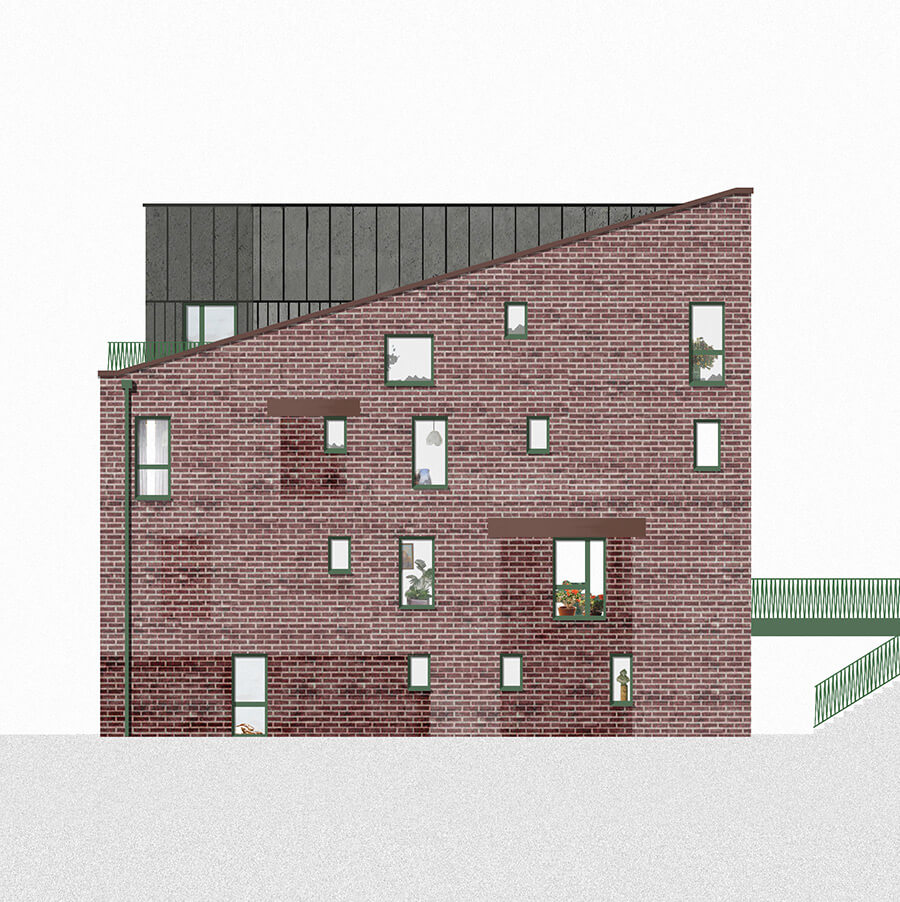

The formal relationship between the monolith block of industrial structures and their surrounding residential streets is an observable trait in the development of Ashton-under-Lyne. It represents an aspect of the heritage which, due to the loss of so many of these monoliths, is increasingly hard to locate in the settlement. The proposed development embodies this relationship in its conscious echo of the formal and material composition of industrial buildings.

The scheme seeks to push back against the policy compulsion to replicate adjacent typologies on back land sites. The previous consents establish a formal precedent, and the current proposal is developed and refined by drawing narrative connections between the formal and material composition and the particularities of place which constitute the heritage.

The building fabric becomes a suggestive document, conveying the principles of the heritage through material memory; industrial form, materiality, and proportion; echoes of the modifications which mark surviving structures of this type. Lyrical and evocative perhaps, but never nostalgic. The resulting formal and material richness delivers a connection with the past which is critical, not reverential.